Empowerment Through Unity: Rethinking Western Attitudes to Development Work

June 2017

This article was written by Annalise Halsall on the Oxford International Relations Society website and has been reproduced by kind permission.

In recent decades, changing discourse from the United Nations has altered the focus of international relations from preventing interstate conflict to furthering the human security of individuals. The UN Development Programme 1994 Human Development Report highlighted these new ideals of “freedom from want” and “freedom from fear” for all people, and claimed that this was the best way to overcome global insecurity. Although this new view of international relations has not changed, international aid in many Western government budgets is currently in the process of being cut. Without this interstate intervention, the burden of facilitating international development falls more heavily onto the third sector: not-for-profit organisations that belong to neither the public nor the private sector. Traditionally value-driven, and reliant on volunteers, charitable organisations are now a growing source of aid for many communities across the world.

The increase in the number of young people travelling to volunteer abroad is just one example of these changing trends. The costs of travel are decreasing, and as more charities offer volunteer abroad projects, optimistic millennials are turning to journeying to developing countries to offer whatever support they can.

Many have heard the tales they regale upon their return. Countless testimonies recount the inspiration they felt due to the positivity of those they went to help, and volunteers often talk of the transformative impact of their experience on their outlook on life. Clearly these volunteers seem to benefit from these schemes, but what about the effects upon those they aim to help? There is a dark underside to all of those sunny photographs on social media. A sceptical view lingers in the minds of many: a fear that these heroic efforts can actually make the situation in these countries worse. If not done correctly, by focusing on the necessities of the people in need, these methods of providing aid to vulnerable communities can lead to the further disempowerment of those we seek to support, and the opposite of the unity we seek to promote.

The plague of voluntourism can be criticised for many reasons, not least because of the danger of faux-orphanages, where conditions are made worse for children in order to provoke the sympathy of visitors and encourage donations. The increase in young and privileged people travelling from the Global North has actually stimulated a market for orphaned children in places such as Siem Reap in Cambodia, which has lead to parents renting out their offspring to faux-orphanages where they take on the responsibility of entertaining visiting volunteers. This is a systematic problem, but there are also emotional and psychological problems created by the influx of voluntourism: the abandonment issues many children have when living in these orphanage institutions are only aggravated with the coming and going of overseas volunteers.

Another danger of voluntourism is its perpetration of the same ideas of colonialism, which is often assumed to be confined to history. Many schemes harken back to the phenomenon of the “White Saviour complex”, as Westerners intervene based on the assumption that they know best about the needs of their “grateful recipients”. Although understated, this issue is no less dangerous. This problem highlights two other concerns: the first is the misinformation about the needs of communities; the second is that building people’s lives around the actions of volunteers in the third sector is fundamentally unsustainable. Voluntourism is inherently a transient enterprise: summers end, gap years eventually turn into a job or university, and communities, having learnt to rely on these strangers, are left in the lurch.

Moreover, the burgeoning culture of providing these “poor passive African children” with aid is one that inherently segregates cultures. It can consolidate the mind-set of White and Western superiority, where we focus on the grace of our own actions and ultimately, neglect the value that these communities hold without us.

the burgeoning culture of providing these “poor passive African children” with aid is one that inherently segregates cultures

Faced with these criticisms, it is easy to conclude that overseas aid ought to be scrapped altogether. However, with or without these dangers, the third sector is vital in furthering the goals of the international community. The UN’s Millennium Development Goals which include eradicating extreme poverty, achieving universal primary education and combating HIV aids are just one example of these aims in action. If we are to reach these goals, we must harness the power and potential that NGOs (Non-Governmental Organisations) have in playing a role to achieve this. By virtue of being smaller and more specialised, these organisations in the third sector have opportunities where states and bureaucracies do not. NGOs are much better able to talk to the communities they wish to help, to spend time understanding their culture and customs, and hence come up with programmes that actually have the potential to address the problems they face. International organisations such as the UN have little choice but to delegate to NGOs and grassroots organisations if they want to see tangible returns to their policies on human security. Cooperation and collaboration on the organisational level will in turn allow for the partnership between not-for-profits and individuals in developing countries. NGOs are able to facilitate the direct provision of aid with a lower risk of corruption than the state or the private sector. Encouraging unity and collaboration across actors in the international field in recognition of their common goals will ultimately help these goals to be realized.

Still, in order for this to succeed, the work of not-for-profit organisations has to be examined. It is easy for charitable organisations to fall into the same traps as any other player in international aid, by assuming they know best, and failing to understand the history and culture of the people they aim to help. Organisations in the third sector have to make use of their ability to form lasting relationships with communities and understand their needs.

It is easy for charitable organisations to fall into the same traps as any other player in international aid

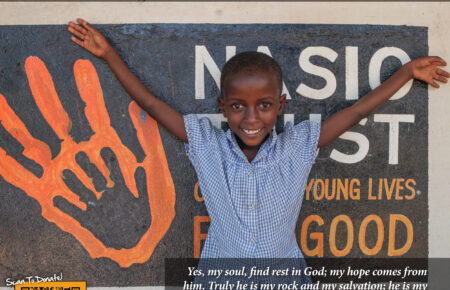

Locally based in Oxford, the Nasio Trust is an organisation that does exactly this. With a focus on children orphaned due to HIV and other vulnerable young people, the Nasio Trust aims to break the cycle of poverty in rural western Kenya by providing education, a daily meal, and medical care. Their innovative approach to providing aid is proving successful.

In speaking to the founder of the Nasio Trust, Nancy Hunt, their philosophy becomes clear. Hunt emphasises the importance of building trust between all parties involved in the aid process. An example of this is the fact that the Kenyan guardians who elect to look after children are not paid in cash – instead they are provided with a house and food, or whatever else will enable them to provide a safe and stable home for the children they’re caring for. They are in turn asked to volunteer for the organisation for one day a week. The results of this, Hunt says, have been clear. The guardians, freed from expectation of handouts from overseas visitors have become empowered and united. The guardians work together to improve their living conditions, and have become deeply invested in the future of both their children and their wider community. One of the children, Rajab, who attended Nasio’s day centres when he was young, now volunteers for the organisation himself.

When it comes to overseas volunteers, the stance of the Nasio Trust is also well defined. They welcome helpers, but are adamant that their communities are not spectacles to be ogled at by tourists. Instead, they organise trips to climb Mount Kilimanjaro, with all of the proceeds from the £3195 fundraising goal going towards the charity’s work. Volunteers wishing to visit Nasio’s work in rural western Kenya must contribute in a practical way. If UK builders travel to Kenya for example, they use their expertise to help build houses; a partnership ensues between UK builders and the local builders in the community. They exchange skills, working together and respecting each other as equals, avoiding any separation of status between the visitors and the locals.

Hunt also highlights the importance of these experiences for those living in the Western world, where political leaders seem to become more and more polarised by the day. In an atmosphere of uncertainty and fear of “the other”, there is value in exploring the world for yourself and recognising that humanity exists beyond the borders of your country: on the most basic level, shared experiences are just one way to encourage unity across societies. But it is of course vital to know the organisation you’re volunteering for, and whether or not their work is in line with your aims. Most important is the need to consider whether the focus of the organisation is to serve the individuals within their care, or whether they fall into the common trap of morphing into a business mostly intent on turning a profit.

In an atmosphere of uncertainty and fear of “the other”, there is value in exploring the world for yourself and recognising that humanity exists beyond the borders of your country

By taking a bottom-up approach, actually communicating with locals and asking them what they require, the Nasio Trust also makes no assumptions about the needs of the communities they wish to serve. They have learned from past mistakes, made by themselves and others. By promoting the unity of common goals and a common status in their relationships, they prove that overseas aid or volunteering does not have to be centred on “the White Saviour”, following the historical pattern of the West disconnecting itself from the rest of the world. Instead, they offer a model and a philosophy that could be adopted by actors on multiple levels, from other NGOs, to the volunteers themselves as they research different schemes.

The lesson is clear for all of us. By prioritising the needs of those we wish to help through the third sector, and by seeking to understand the lives and culture of the people receiving aid, we can maximise the impact of our actions. The benefits of this reach far beyond ourselves, to fostering unity across societies, promoting human security in international relations, and most importantly, having a lasting effect on those who inspired the action in the first place.

Discover more about volunteering with the Nasio Trust in Kenya at volunteerforcharity.org.

This story is listed in: About Nasio, Press